Seductive Optics and Skeuomorphic Intelligence

Things are not always as they seem. Artificial intelligence is like that. Steve Jobs famously directed Apple’s designers to precisely imitate the napa leather seats in his Gulfstream jet to adorn the iCal app. The result was a seemingly supple and needle stitched interface that, nevertheless, felt like glass. The interface for the iPhone was famous for these expertly crafted, “lickable” icons that were rendered with artificial shadows and depth. Skeuomorphism became the term of art for this habit of borrowing design cues from the physical world to make their digital counterparts attractive and recognizable. In time, designers embraced “flat design”, a style ostensibly more suited to its medium. But the faux leather and superficial resemblances carry on.

Skeuomorphism, as wonky as it sounds, is a simple concept. It’s the idea that new designs retain ornamental elements of past iterations no longer necessary to the current objects’ functions. You see this often in Apple’s software: The Notes app is presented as a yellow legal pad, while Game Center is modeled after a Las Vegas-style casino table, with lacquered wood and green-felt cloth.

Austin Carr, “A Former iPhone UI Designer Defends Apple’s Fake-Leather Design Philosophy” at Fast Company

The effort to mirror objects in the world in our artistic creations reaches back into prehistory, from cave paintings and rock sculptures to the latest 3D rendering engine or animatronic sexbot. Whatever the medium, as our tools and skills increase, we are able to make ever more convincing replicas of the genuine article. Today, because of these superficial similarities, we are often fooled into thinking that the artificial intelligence programmed into many of our creations isn’t artificial after all. This misapprehension is the result of being taken in by a magic trick, by a kind of skeuomorphism that Robert J. Marks calls, “seductive optics”. Skeuomorphism is not restricted merely to computer interfaces and virtual artifacts. It is …

… a term which refers to the fashioning of artifacts in a form which is more appropriate to another medium. Archeologists often use it to explain the existence of otherwise inexplicable objects. Some of those might be the fake copper rivets on jeans, long made obsolete by modern stitching. Radiator grilles on electric cars. Plastic hair combs dyed to look like tortoiseshell. A camera phone which emits a shutter-click sound. A modern sports car which must meet noise regulations, but pipes in racy sounds through its speakers to console its driver.

“Who Misses Skeuomorphism” at the Language, Learning and Culture Blog

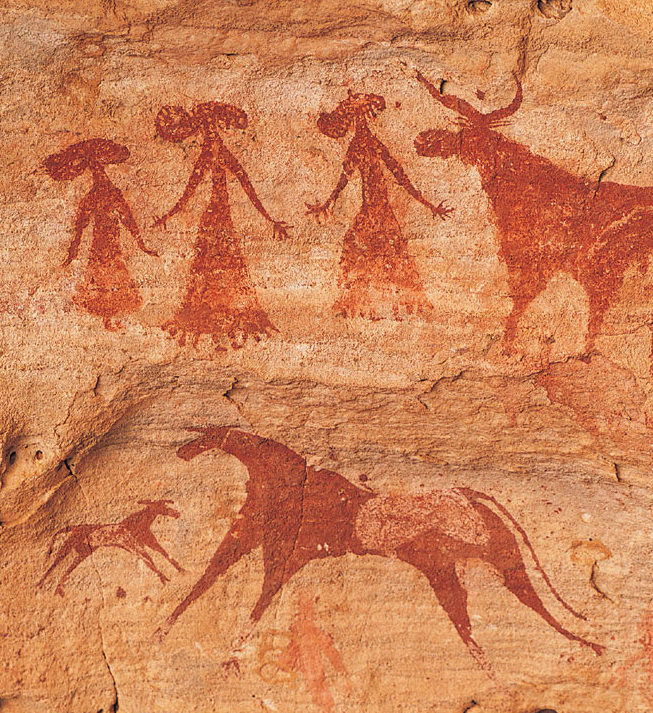

Painting People

Early humans sometimes depicted the drama of the hunt on cave walls by scraping or smearing charcoal and pigment. Others assembled or chipped at rocks to make human effigies. Some of these artifacts are more sophisticated than others, showing movement and depth. Still, no one would think these simple caricatures or the rocks themselves shared the conscious lives they represent. These are plainly soulless, lifeless rocks with no thoughts, hopes, or sorrows.

By the late Renaissance, artists had greatly improved their brushes, pigments, and media as well as their understanding of perspective, foreshortening, underpainting, and shadows. Their artworks captured complex scenes and often the mood of their subjects. We may not know the secret thought behind Mona Lisa’s smirk, but Leonardo Da Vinci’s relatable portrayal does make us wonder. Van Eyck’s perfectly painted portraits, with wrinkles and warts, make us feel all the more like we can know something of the subject, or that we can peer into the Girl with the Pearl Earring’s eyes and share her longings.

Oranges are just one item from an almost infinite list of things seen by Van Eyck with amazing acuity … the textures of fur, flesh, wood, stone and ceramics, the exact pattern of body hair, follicle by follicle, on Adam’s naked body, the precise hue and shape of a wart on a clergyman’s cheek, and so on.

“How Jan van Eyck revolutionised painting” by Martin Gayford at The Spectaotr (February 8, 2020)

With increasingly formalized training in academies, artists mastered realism. The subjects of French Academic Realism are so true to life that it is hard not to empathize with them, to storm the Bastille with them, or even to lust after them. Seductive optics indeed.

Jan Van Eyck

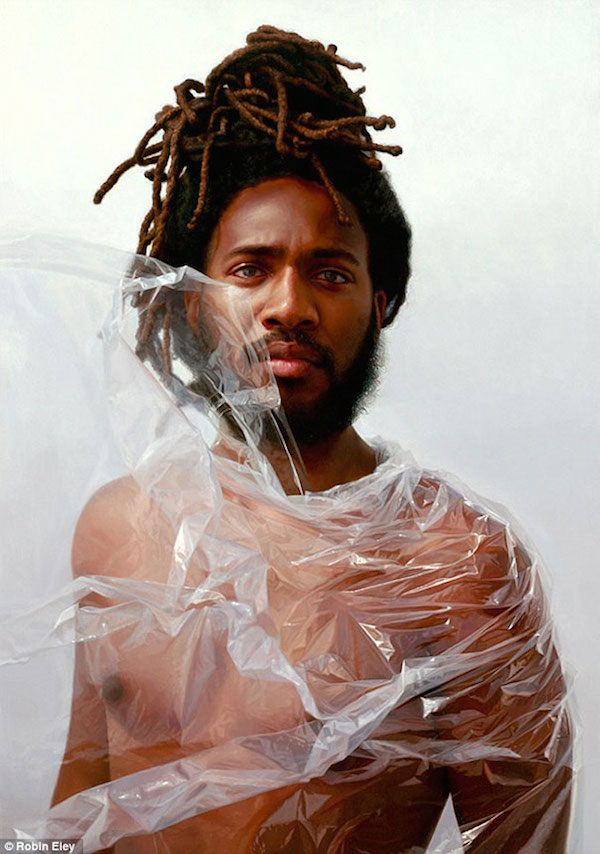

Today, a subgenera of painters and sculptors called hyperrealists take it even farther, reveling in their ability to capture the most difficult of subjects in a way that is indistinguishable from a photo or living person. Their dramatic skills often lead admirers to exclaim that the subjects look more real than reality, or at least more so than a photograph.

I’m mesmerized by this remarkable artistry. I can watch these artists perform their magic for hours on the web. Still, because each of us has worked with play dough and paints, we know the basics of the process behind these pieces. We know that these images and forms have no more inner life than the oil or clay that comprise them. The highlights and shadows painted into the painting are not the product of three dimensionality or the light cast in the gallery. The light that illumined the artist’s subject is, in this medium, entirely illusionary.

Though they may be visually indistinguishable from a man or woman, passing the art equivalent of a Turing Test, we know that these portraits are not in the least the same kind of thing as what they portray. Whatever emotions we see in them is projected on them by us. Paint does not suffer. Stone does not breathe.

Dear God! How beauty varies in nature and art. In a woman the flesh must be like marble; in a statue the marble must be like flesh.

Victor Hugo, Victor Hugo’s Intellectual Autobiography: Being the Last of the Unpublished Works and Embodying the Author’s Ideas on Literature, Philosophy and Religion “Hyperrealistic Sculptures Blur the Line Between Clay and Flesh”

The incredible skills reaching the apex of imitation with paints on the canvas are, likewise, achieving stunningly convincing portraits on the screen via computer graphics.

Moving Pixels

Computer animation has followed a similar trajectory toward realism. Early animations were as crude as rock carvings, limited as they were by relatively weak CPU’s, as yet undeveloped rendering engines, and a lack of digital artists. The monochromatic Space Invaders was endlessly playable, as were the whirling, 8-bit dervishes of Centipede and the bubble-gumless, three-dimensional spaces of Duke Nukem. But the graphics were a million pixels from virtual reality.

Now decades and countless iterations in, with enormous human capital and ingenuity invested into motion graphics and GPUs, the optics are seductive and engrossing. Head phones on and eyes glued to the screen, it’s easy to get lost in the sprawling world and epic narrative of Mass Effect, or to feel that you are attacking the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen with an M1 Garand rifle, your rag-tag squad assisting. With each iteration, game developers make strides in simulating the unique recoil of each gun model, the aural pattern of explosions near versus far, the game physics of spilt blood and bent grass underfoot, and the fraying edges of a soldier’s ribbon bars, specific to rank and nation.

Bravo! Charlie! It’s amazing. It’s an adrenaline rush. And it’s all artifice. These animations are becoming ever more realistic, but not in the least bit more the kind of thing which they represent.

In addition to cosmetic advances, motion capture technology has traveled far. Painstaking attention to plotting our distinctive expressions and gaits has greatly increased the appearance of natural movement. Ever since Andy Serkis so convincingly gave life to Gollum, recordings of humans in motion have supplied the scaffolding for countless characters.

In animation … everything is fabricated. … Every moment. Every scratch and look. Everything is a discussion. There are no gifts. There are no happy accidents … It was useful having the live action performance reference. We’d pull them up in front of the animators and say, look at what’s happening here. Little twitches underneath the eyelid, little things that are involuntary became very important.

Gore Verbinski, “Rango Behind the Scenes: Breaking the Rules” via Margaret X at YouTube.

One of the joys as a viewer is having that dawning recognition of a familiar actor who has been reincarnated as Puss in Boots, Shrek the ogre, or Mator the tow truck. The idiosyncrasies and ticks of the human originals are prized source material for the animators. So, Kristen Bell’s signature phrase — “Wait, what?” — and her habit of biting her lip is mirrored in Anna of Arendelle. Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson’s brow wave personalizes Maui. Although these beloved characters are singing and dancing and joking along, like Mona Lisa, the image is a mirror. It is derivative, with no life of its own.

Whatever emotions we bring to the movie or to the game ourselves, our digital allies and enemies breathe no breaths, make no sacrifices, feel no lonely deaths.

Because the textures that skin them and algorithms that animate them are more sophisticated, it is tempting to think that the ducking and evading Juvies, Pouncers, and Swarmaks of Gears of War are more intelligent than Pac Man’s nemeses: Blinky, Pinky, Inky and Clyde. One might think that whereas the ghosts that haunted Pac Man had a wisp of personality, the villainous grunts of a modern first-person shooter have a measure more. Surely, in some future game, the imitation will be perfected. Game AI will continue on this trajectory and surpass human intelligence, just as Watson bested Kasparov. But the truth is, none of these avatars possess any inherent intelligence whatsoever. They too are void of thought.

We’ve erected this elaborate system of gears and pulleys using electronic nodes. The number of these levers that we can fit on a circuit is mind boggling. At the push of a button and the tilt of a joystick, these systems are able to reenact remarkable routines that the human programmers have strung together. But as the less exhaustively routinized NPCs (Non-Playable Characters) in the game betray, if the programmer hasn’t yet written the routine, the character will be left kicking blindly into a wall.

Talking Boxes

In recent years, we have witnessed a dramatic leap forward in mimicking the primary tool humans use to communicate: speech. Increasingly, our internet connected devices can recognize speech, translate the intent of the speaker, respond using recorded and synthesized voices, and integrate with services that order a pizza or change the thermostat. When we were pushing buttons to control our devices, we were more likely to think of them as behaving mechanistically, as being levers and pulleys at bottom. As dramatized by Joaquin Phoenix and Scarlett Johansson in Her, these voice boxes are a whole new soundscape of seduction. This aural interface can create a powerful illusion.

Each component of the trick is key: speech recognition to receive input, Natural Language Processing to translate verbal requests into commands, third party API’s to execute them, and speech synthesis to respond.

Speech recognition is the pledge of this illusion: “I hear you.” The first system, Audrey (1952), could only recognize numbers zero through nine, and at that, for best results, only from a particular speaker. It would be decades before speech recognition could pick out the key words in a human sentence spoken clearly by most anyone. Using machine learning on enormous data sets, speech technology can now generalize over many nuances and varieties of human speech.

Before we anthropomorphized these programs as Alexa, Siri, and Cortana, the earliest iterations sounded far from human. To WOPR in War Games, the dissonant screeching of a dial-up modem to establish a connection was a perfectly adequate “Hello!” But to us, its invitation — “Shall we play a game?” — sounded obviously synthetic and impersonal. Early versions of text-to-speech software sounded equally robotic. The words, pieced together individually, lacked the lilting, cadence, and emphasis of human speech. So too if you select this text on Mac OS, right click, and select “Start Speaking”. Progress, but a ways to go.

So far, success in humanizing speech technology has been mostly achieved by recording vast libraries of spoken words and phrases. A few melodious speakers enjoy full-time jobs giving voice to our assistants, recording sentences and word pairings day after day. Voice packs featuring celebrity voices became popular on navigation devices in the aughts and are now making their way onto the voice assistants from Amazon, Apple, and Google. For a small fee, you can interact with a disembodied version of the once inimitable Samuel L. Jackson. No doubt the distinctive voices of others will follow.

There will be synthesized versions of gravelly voices, deep baritones, fast talkers, low talkers, high talkers, yada, yada, yada. Indeed, Amazon has added functions to its Speech Synthesis Markup Language (SSML) to enable Alexa to whisper, emphasize a word, or mimic local slang.

Talking to your Amazon Alexa is cool, but sometimes her responses can be robotic. (Just because she’s an AI doesn’t mean she has to sound like an AI, right?) Amazon hopes to change that by giving developers the ability to hone Alexa’s responses with “a wider range of natural expression.”

Christina Bonnington, “Alexa’s responses are about to get more human” at The Daily Dot

But even with untold hours of research, anticipating questions, and preprogramming responses, the limits of these systems are easily discovered. The most basic commands are often mistranslated. Memory of previous commands doesn’t guide current commands. The jokes are evidence of preprogramming, not of a sense of humor. (If you ask Alexa what its preferred pronoun is, it replies, “I am female in character.”) The many gaps in that programming leave these digital assistants grasping at the Web for what humans have said on the matter. Our talking boxes run their routines but understand nothing, whether or not they’re made in China.

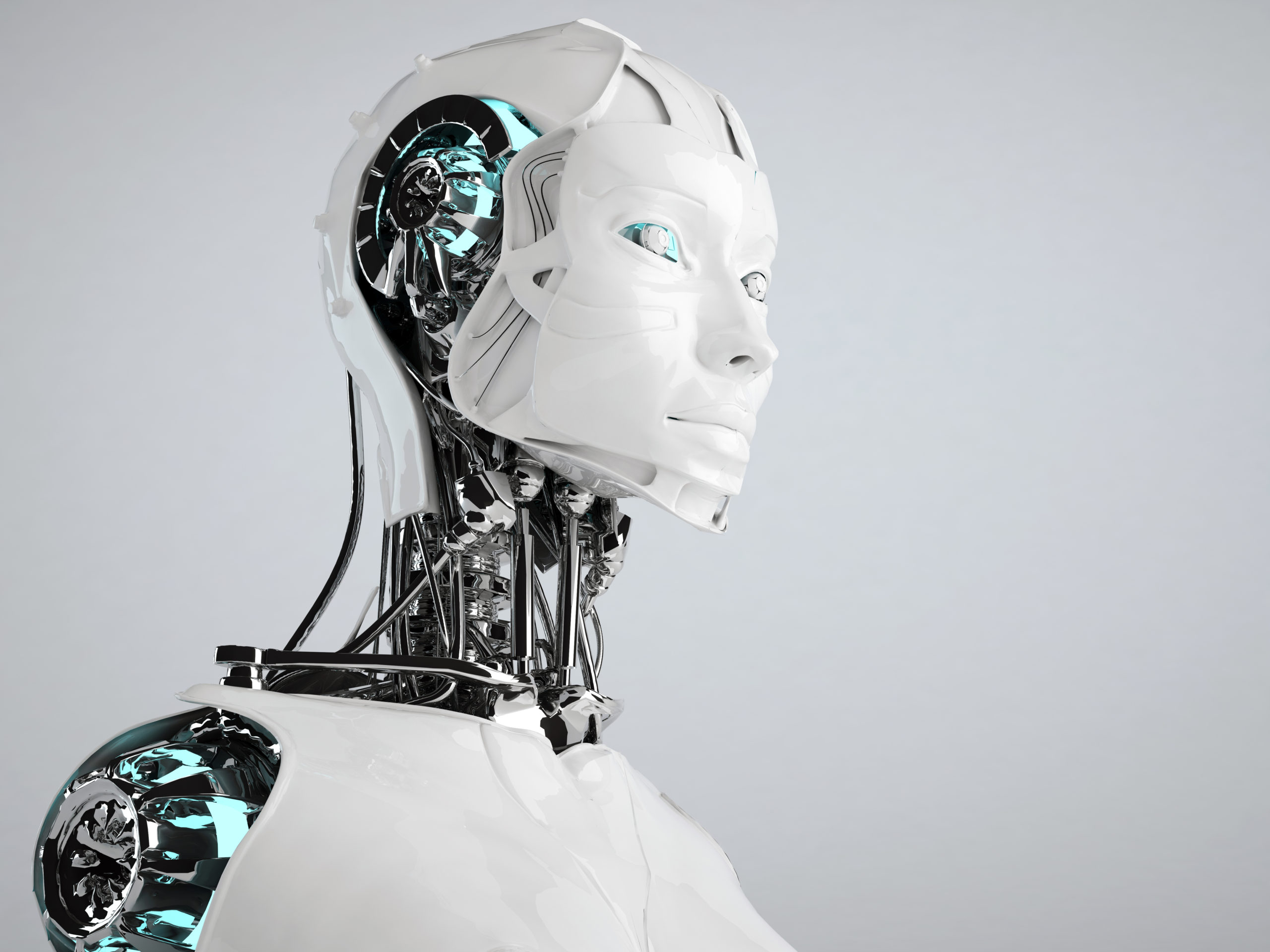

The Composite

The greatest aspiration of artificial intelligence Frankensteins is stitching together all the sundry parts into a moving, talking, seeing, and interacting android. Today, this composite of technologies is most famously embodied in Sophia. This android from Hanson Robotics is an international “celebrity”, appearing on late night shows and on the exhibit floors of tech conferences.

With how many things are we on the brink of becoming acquainted, if cowardice or carelessness did not restrain our inquiries.

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

On its marketing page, Sophia’s marketing department puts the following words in its mouth, as though it has a sense of self and is speaking in the first person.

In some ways, I am human-crafted science fiction character … In other ways, I am real science, springing from the serious engineering and science research … In their grand ambitious, my creators aspire to achieve true AI sentience. Who knows? With my science evolving so quickly, even many of my wildest fictional dreams may become reality someday soon.

“Sophia“, Hanson Robotics (March, 2022)

With a knowing wink, the programmers for Sophia have dubbed its operating and networking system the Synthetic Organism Unifying Language: SOUL. Sophia continues: “Recently my scientists tested my software using the Tononi Phi measurement of consciousness, and found that I may even have a rudimentary form of consciousness, depending on the data I’m processing and the situation I’m interacting in!”

Whatever may be the case, and whatever dubious presuppositions underwrite Hanson Robotics’ claim of rudimentary consciousness, it is a mistake to think that Sophia’s human resemblance justifies it any way.

If you’re inclined to think, based on appearances, that Sophia or the android above are more likely to be conscious than an assembly line robot or the vehicle you drive, you’ve been schnookered by seductive optics. Your vehicle has far more lines of code than Sophia and its development process and basic ingredients are the same. Looks can be deceiving, and in this case most assuredly intend to be so. Though it’s still stuck in the uncanny valley, Sophia’s facade and feminine figure are more disarming than the metal frame beneath its “frubber” skin, which still resembles a T-800 on the assembly line before receiving its “living tissue over a metallic endoskeleton“.

It is possible that at some time this might be done, but even supposing this invention available we should feel there was little point in trying to make a “thinking machine” more human by dressing it

Alan Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” (1950)

up in such artificial flesh.

Thinking that Sophia’s wink is a come-on, that it can laugh at its own jokes, or that it could be surprised at a new insight, is like thinking your computer’s “Desktop” can be chopped up to be used as kindling, that documents in the “Recycle Bin” will someday be reused as coffee cups, that Mac’s startup “hello” is a warm greeting, and that it is self-aware when it introduces itself on the local area network as “iMac-208c”. These skeuomorphisms we use from human behavior obscure the categorical chasm between the real and the replica. In truth, Alexa and Sophia are no more conscious or intelligent than Mona Lisa. But the microchip, the machine language, and the algorithms lie behind the veil in darkness, and we are more easily seduced.

There is no subject in which men have always been so prone to form their notions by analogies of this kind, as in what relates to the mind. We form an early acquaintance with material things by means of our senses, and are bred up in a constant familiarity with them. Hence we are apt to measure all things by them; and to ascribe to things most remote from matter, the qualities that belong to material things.

Thomas Reid, “Essays on the Intellectual Powers of the Human Mind” (1785)

In Our Own Image

Thousands of years ago, the Hebrew prophets mocked the idol makers of their day for bowing to worship their own humanoid sculptures. They joked that in addition to being blind and mute, these idols were made from the same pile as their fire wood. The idols could not know nor understand, much less act upon a prayer or plea. This taunt has less resonance now. Our creations can “listen”, so to speak. They can “see”, from a certain point of view.

In Frank Herbert’s Dune, in the aftermath of a war with AI machines, The Great Convention commands: “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind.” This science fiction storyline is plausible to us because of the huge strides we have made in imitating human behavior. But we ought not be taken in by appearances. As of yet, there’s no reason to think that our more svelte and capable androids and avatars are more alive or aware than the totems and effigies of our ancestors. Mona Lisa smiles, but she is not happy. Sophia speaks, but she knows not what of.

Note: I have included several works from artists to illustrate the distinctly visual nature of seductive optics. All living artists above are linked and the reader is encouraged to follow and explore their work.